New Science of Learning

New Science of Learning

New Science of Learning Task Force: Shirley Ashauer, Brian Bergstrom and Dustin Nadler.

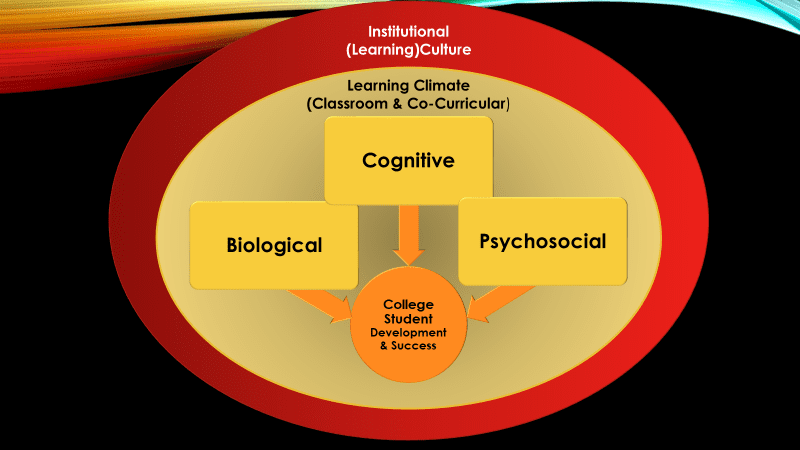

The Science of Learning: Interconnected Systems

Imagine a student sitting in your 9:30 a.m. Monday class, struggling to pay attention and engage in the classroom conversation. As you observe her nonverbals, you wonder “Why doesn’t she seem engaged in class today?” And as you search for possible explanations, have you considered any of these . . .

Her performance in the classroom will be influenced by her biology and cognition: whether she ate breakfast this morning or had coffee, whether memory is compromised by a night of poor sleep, or perhaps whether she is taking medications for depression, anxiety, or attention.

From a psychological perspective, her learning will be influenced by the way she conceptualizes her classroom experience and her expectations (e.g., beliefs about her academic aptitude, expectations for the course, her sense of how the course relates to life/career), real-time mental competition for her attention (e.g., mind-wandering thoughts about a love interest, an ailing parent, a new Netflix series, an upcoming shift at work), or moods that are calibrated by friends (lost or gained in the transition to college).

In the sociological domain, the student arrives in class having been influenced for years by the social norms and personal history associated with her gender, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, religious affiliations, the occupation and income of her parents, and so on.

And all these are, in turn, influenced by the larger culture: the classroom climate, the institutional culture, the current political climate, the economics of paying for college, any smart-device technologies through which she communicates and shares herself, and the television, movies, music, novels, poetry, and paintings that have shaped her identity and molded her values.

Whew. . . that’s a lot to consider with the question, “Why doesn’t she seem engaged in class today?”

Learners as Biopsychosocial Systems

Influences on Learning: Psychosocial, Cognitive and Biological

The new science of learning considers all these factors in students’ learning – the interrelationships of cognitive, psychosocial, and biological influences on learning processes. As learners, we are biopsychosocial systems. That is, as learners, we don’t learn in a vacuum; at any given moment, our thoughts, actions, and motivations represent the convergence of multiple systems and environmental factors.

In the New Science of Learning, we consider how these systems may interact to impact our students’ learning. We provide links to websites, videos, books, and practical applications and suggestions that we hope are helpful to you in your course design, course facilitation, and development of assignments and learning assessments.

We hope these resources will be helpful to all stakeholders on campus – faculty, staff, students, and leadership teams. Feel free to explore the links for practical applications grounded in the science of learning as we continue to collectively evolve our learning culture at Maryville.

- Psychosocial Influences on Learning: Science of Mindsets and Learning

As educators, how can we create the conditions for students’ willingness to take academic risks, experiment, and use failure as an opportunity for learning? The new science of learning has shown that students’ individual beliefs and assumptions about learning are important to their academic achievement and growth. Simply put, mindsets matter.

Mindsets that affect students’ capacity for learning include: (1) students’ beliefs about where responsibility for learning and emotions resides (“the professor didn’t give me a study guide and so I didn’t do well” versus “I need to figure out an effective study strategy so that I can do well in this class”), (2) beliefs about failure (“mistakes demonstrate that I’m incompetent” rather than “mistakes are opportunities for learning and growth”), and (3) beliefs about the nature of knowledge itself (knowledge claims are the purview of the experts – versus all members of an academic community can critically assess knowledge claims). In this section, we offer an overview of the science of mindsets – and practical guidelines to foster adaptive mindsets through effective teaching and learning strategies.

- Science of Self-Authorship and Self-Regulation

What is it? ∣ How can we facilitate it? ∣ Interested in learning more?

What is Self-Regulated Learning and Self-Authorship?

Have you ever heard this comment from a student? “That professor can’t teach. I wish he would just get to the content and lecture. Sometimes, I feel like I’m teaching myself.” Or: “That professor didn’t provide a study guide for the exam, and I ended up with a ‘C’ on the exam. She makes me so frustrated.”

Students often arrive to college, fully prepared to take notes on lectures and acquire (without question) the knowledge that experts possess. Yet, the ability to critically evaluate evidence, construct new knowledge, make informed judgments, and take responsibility for behaviors and emotions are essential skills of autonomous thinkers who can take responsibility for their learning. In this section, we provide the most effective, evidence-based teaching and mentoring strategies for challenging and supporting students to develop into autonomous, self-authored learners, based on research from:

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Social cognition

- Developmental psychology

- Discovery-oriented learning

- Inquiry-based learning

Self-regulated learning is the self-directive process by which students become autonomous learners who can take responsibility for their learning, emotions, and behaviors. When students understand their role as an agent (the one in charge) over their emotions, thinking, and learning behaviors, they are more likely to take responsibility for learning. Instead of saying, “the professor made me mad,” they can take responsibility and might say something like: “I’m frustrated that I did poorly on the exam, and would like to learn from this. I’m going to take charge and meet with the professor to learn what I might do differently to improve on the next exam.”

Self-regulated learning is the self-directive process by which students become autonomous learners who can take responsibility for their learning, emotions, and behaviors. When students understand their role as an agent (the one in charge) over their emotions, thinking, and learning behaviors, they are more likely to take responsibility for learning. Instead of saying, “the professor made me mad,” they can take responsibility and might say something like: “I’m frustrated that I did poorly on the exam, and would like to learn from this. I’m going to take charge and meet with the professor to learn what I might do differently to improve on the next exam.”Discovery-oriented teaching strategies promote the development of autonomous functioning by engaging students’ authentic curiosity to explore solutions to important problems in which they are interested.

Passive teaching strategies, on the other hand, (providing students with the answers and giving them little voice or choice), can limit students’ opportunities to develop the self-regulation skills needed to take responsibility in the learning process.

The APA website provides a summary of practical, evidence-based instructional practices on what educators can do to inspire curiosity, creativity, and lifelong autonomous learning: Developing Responsible and Autonomous Learners: A Key to Motivating Students -Teacher’s Modules.

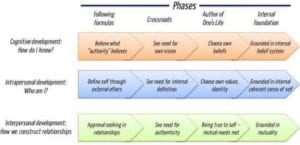

Self-authorship is the broader mental structure that enables self-regulation, and is comprised of cognitive, social, and intrapersonal components. A self-authored individual is self-directed, self-initiating, and has developed their own internal seat of judgment or “governing system.” In the intrapersonal realm of their development (who am I?), self-authored students’ beliefs and values are internally grounded. They are able to openly engage challenges to their own views and beliefs. They are able to take responsibility for their own emotions, choices, and learning – rather than blaming others for their feelings or poor learning outcomes. (They are more likely to say, “I am frustrated by the situation” – rather than “the professor made me mad” – recognizing that they are responsible for (and have control over) their own emotional reactions to a situation.)

Self-authorship is the broader mental structure that enables self-regulation, and is comprised of cognitive, social, and intrapersonal components. A self-authored individual is self-directed, self-initiating, and has developed their own internal seat of judgment or “governing system.” In the intrapersonal realm of their development (who am I?), self-authored students’ beliefs and values are internally grounded. They are able to openly engage challenges to their own views and beliefs. They are able to take responsibility for their own emotions, choices, and learning – rather than blaming others for their feelings or poor learning outcomes. (They are more likely to say, “I am frustrated by the situation” – rather than “the professor made me mad” – recognizing that they are responsible for (and have control over) their own emotional reactions to a situation.) In the cognitive realm of development (how do I know?), these students are independent, critical thinkers who no longer unquestioningly accept experts’ knowledge claims, but rather use their own internal processes for assessing knowledge claims based on evidence or a critical analysis of the theoretical rationale. In the social domain of development (how do I construct relationships?), they no longer have a need to please others or gain their approval to maintain their self-esteem. Rather, they are able to engage in relationships grounded in mutuality (learning is a mutual process), take multiple perspectives, and develop intercultural maturity. In short, a self-authored student is an independent thinker who takes responsibility for their learning and emotions, no longer unquestioningly accepts experts’ knowledge claims or depends on authorities for the “right” answer, and is self-directed and self-motivated.

In the cognitive realm of development (how do I know?), these students are independent, critical thinkers who no longer unquestioningly accept experts’ knowledge claims, but rather use their own internal processes for assessing knowledge claims based on evidence or a critical analysis of the theoretical rationale. In the social domain of development (how do I construct relationships?), they no longer have a need to please others or gain their approval to maintain their self-esteem. Rather, they are able to engage in relationships grounded in mutuality (learning is a mutual process), take multiple perspectives, and develop intercultural maturity. In short, a self-authored student is an independent thinker who takes responsibility for their learning and emotions, no longer unquestioningly accepts experts’ knowledge claims or depends on authorities for the “right” answer, and is self-directed and self-motivated. The following website provides curricular and co-curricular resources for engaged learning to facilitate a student’s development toward self-authorship: http://www.units.miamioh.edu/EngagedLearning/promote.html.

An additional website that provides recommendations on teaching and learning strategies to foster self-authorship is as follows:

https://selfauthorshipcmu.wordpress.com/2016/10/28/session-3-teaching-learning-activities/Lastly, to hear about how to assist students in progressing from external formulas to developing their own internal voice and taking responsibility for their learning, check out this short podcast, featuring Marcia Baxter-Bagolda.

How Can We Facilitate Self-Regulated Learning and Self-Authorship?

Course Design ∣ Course Facilitation ∣ Course Assignments ∣ Learning Assessment

Course Design

Some websites and articles for course design to foster self-regulated learning and self-authorship:

■ “Engaged Learning for Self-Authorship.” This website provides frameworks for curriculum and course design to foster self-authorship through engaged learning: units.muohio.edu/EngagedLearning■ “Integrated Course Design.” This article discusses how to take a systematic, learning-centered approach to integrated course design: https://selfauthorshipcmu.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/idea_paper_42.pdf

■ “Designing Learning Experiences: Start with the Student and Co-Create:” This article describes how

educators can use technology to create an environment in which student interest drives the learning process:

https://www.edutopia.org/blog/designing-learning-experiences-student-co-create-matt-levinson

Additional suggestions to foster self-regulated learning and self-authorship through course design:

■ Be explicit in the syllabus and on the first day of class to frame the expectations about what you will be doing and why you will be doing it. For example, let students know up front that you will be using discovery-oriented learning versus passive learning strategies.■ Honor voices from the student’s past of what instructors have told them and consider where the student currently may be, developmentally. Move students from the notion that the professor is the expert who prescribes what to do to a different place where the student explores questions to important issues about which they are genuinely curious. If you are transparent and up front with them about these new expectations, they are less likely to think “the teacher doesn’t know how to teach – why don’t they just lecture and get to the content.”

■ Involve students in setting their own learning goals through guided class discussions. You can set the overarching learning outcomes, but offer possible options about different individualized learning goals that students might set for themselves so that they have a voice in their own learning process.

■ On the first day of class, break out students into groups, and invite them to discuss any recommended changes they have to the syllabus – with the guideline that the recommendations should improve learning. Ask each group to report out their suggestions to the whole class, and work together to co-create the changes to the syllabus that will support this group of students’ learning. This approach is intended to model a stance of shared responsibility in learning on the very first day of class. In addition, ask students to write on index cards a few things about themselves on the cards to help you get to know them. Then, on the back of the card, ask them to write any additional suggestions for changes to the syllabus that would support learning. This additional step ensures that all voices are heard, as sometimes students won’t feel comfortable offering their suggestions in large classes on the first day. Share the additional suggestions during the next class meeting, and jointly determine if you think they will help the group’s collective learning (and then modify the syllabus accordingly).

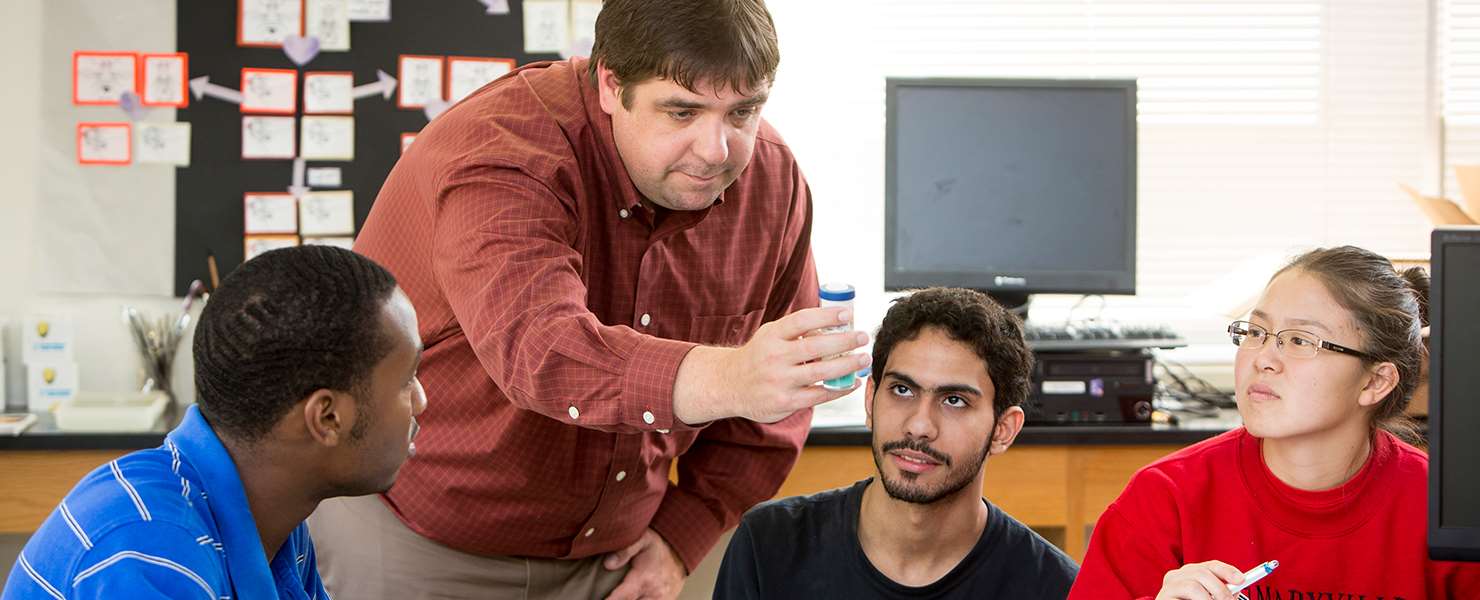

Course Facilitation

Websites and articles for course facilitation strategies that foster self-regulated learning and self-authorship:■ This website provides tips on how to use foster self-authorship in the classroom: https://selfauthorshipcmu.wordpress.com/how-do-we-use-selfauthorship-in-the-classroom/

■ “Putting Students in Charge to Close the Achievement Gap.” This article shows how a school in Pittsfield, New Jersey has become an incubator for an experiment in school reform through engaged learning strategies – student-led discussions, small group work, individual projects, and building a strong connection between academic learning and real-world experience. http://hechingerreport.org/content/putting-students-charge-closeachievement-gap_17676/

■ “Teaching Strategies: How to Stimulate Curiosity.” This article describes 3 practical ways to use questions and information gaps to stimulate curiosity and autonomous learning: https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/28074/how-to-stimulate-curiosity

Additional suggestions for fostering self-regulated learning and self-authorship through course facilitation:

■ Encourage students to make their reasoning explicit during classroom conversations, and help them reflect on where that knowledge comes from (from experts – or from their own internal voice in which they evaluate evidence, theory, and others’ perspectives). Model metacognition by talking aloud about your thinking while working through a problem so that students learn how to make their own thinking explicit. Model for them how to state the logic, rationale, or evidence to solve problems and assess knowledge claims■ Empower students to take the lead in team inquiry discussions on topics in science, math, and humanities that represent real world problems. Support and challenge them to expand their thinking and by taking multiple perspectives when investigating questions and problems of interest to them. http://www.apa.org/education/k12/learners.aspx

■ Encourage students to work collaboratively with peers and you to find answers to their questions – rather than telling them the answers. Provide guidance on how they can do so.

Course Assignments

Websites and articles with general guidelines for course assignments that foster self-regulated learning and self-authorship:

■ This website provides suggestions on teaching and learning activities to foster self-authorship:

https://selfauthorshipcmu.wordpress.com/2016/10/28/session-3-teaching-learning-activities/■ This website provides an engaged learning course example to support students’ development of self-authorship: http://www.units.miamioh.edu/EngagedLearning/courseexample.html

■ This website provides a list of resources and examples of practices to foster self-authorship in the classroom: http://www.units.miamioh.edu/EngagedLearning/ExamplesOfPractice.html

Additional suggestions for fostering self-regulated learning and self-authorship through course assignments:

■ Design the course in such a way that students are given opportunities through assignments to develop their own learning goals, make plans, and apply self-regulation strategies to achieve the goals (such as rewarding themselves after accomplishing a goal). A self-regulation strategy assignment can be embedded in the course, such as the following: Duckworth, A.L., Grant, H., Loew, B., Oettingen, G., & Gollwitzer, P.M. (2011). Self-regulation strategies improve self-discipline in adolescents; Benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions. Educational Psychology, 31 (1), 17-26.■ Create discovery-oriented, authentic learning assignments and experiences in which students conduct research on important, course-relevant questions about which they are genuinely curious.

■ Concept map assignment: Ask students to create a concept map about what they are learning in one class and draw connections to concepts they are learning in other courses. For example, what how do the concepts you are studying biology relate to one another – and how do those concepts relate to concepts in your other classes (history, English, math, psychology, etc.)? This process fosters interdisciplinary

■ Concept map assignment: Ask students to create a concept map about what they are learning in one class and draw connections to concepts they are learning in other courses. For example, what how do the concepts you are studying biology relate to one another – and how do those concepts relate to concepts in your other classes (history, English, math, psychology, etc.)? This process fosters interdisciplinary

thinking and a more cognitively complex perspective.■ Provide developmentally appropriate choices on assignments. Show students how to make learning choices and evaluate the positive or negative outcomes of their choices. For example, a student might select an advanced topic in biology to research, but then struggle with the project because they are unfamiliar with some of the more complex concepts. You could guide them toward a similar topic that requires less advanced knowledge – or to source where they can learn the more advanced concepts (if they are developmentally ready to do so).

Learning Assessment

Website with suggestions on learning assessments that foster self-regulated learning and self-authorship:

■ This website provides recommendations on feedback and assessment to foster self-authorship:

https://selfauthorshipcmu.wordpress.com/2016/11/19/session-4-feedback-assessment/■ In this article on giving students more responsibility for their own learning, a school in Pittsfield,

New Jersey has replaced the traditional grading system with a matrix of competencies of the knowledge and

skills students are expected to master in their course. They use an online database to track individual student

growth. Students are expected to develop critical thinking skills (and not just rote knowledge) required for

success: http://hechingerreport.org/content/putting-students-charge-close-achievement-gap_17676/■ Alex Wulff asks students to grade themselves on their class participation, rather than him assigning the grade.

This approach enables students to reflect on their own performance and critically assess it. Alex notes that the students are often far harder on themselves than he would be, and the process opens up a conversation between him and the student about how they can improve.

Interested in Learning More? – Relevant Books on Self-Regulated Learning and Self-Authorship

Vohs, K.D., & Baumeister, R.F. (2016). Handbook of self-regulation, 3rd ed: Research, theory and application. New York, New York: The Guilford Press.

Zimmerman, B. & Schunk, D.H. (2001). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theory, research, and practice, 2nd ed. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum. Boekaerts, M.

Boekaerts, M. Pintrich, P.R., & Zeidner, M. (2005). Handbook of self-regulation, 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Baxter-Magolda, M., & King, P. M. (2004). Learning partnerships: Theory and models of practice to educate for self-authorship. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Baxter-Magolda, M. B. (1999). Creating contexts for learning and self-authorship: Constructive-developmental pedagogy. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Baxter-Magolda, M.B., Creamer, E.G., & Meszaros, P.S. (2010). Development and self-assessment of self-authorship: Exploring the concept across cultures. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Science of Growth Mindset and Goal Orientation

What is Growth Mindset and Why Does it Matter?

Recently, researchers have begun testing large-scale interventions that target students’ beliefs about whether intelligence can be developed (growth mindset) or whether it is innate and can’t change all that much (fixed mindset). While this research is still in the early stages, the findings have been promising – particularly as they relate to the beneficial impact on academic outcomes for first generation students, students of color, and females in STEM fields. In a related stream of research, students’ goal orientations (the goals to which they focus their attention in academic situations) follow from their mindsets. Goal orientation has been shown to impact adaptive learning strategies (problem-solving, active coping, perseverance) and ultimately academic performance.How Does Goal Orientation Influence Students’ Willingness to Take Risks and Make Mistakes in order to Learn?

When learning new tasks or working on complex or ambiguous problems, students will inevitably make mistakes, which may be embarrassing or threatening to their self-image. These image costs may be at the core of what inhibits learning in group settings such as classrooms (and in organizations, more generally speaking). When instructors (or leaders in organizations) orient students (or organization members) to mastery goals (to view unsolved problems as challenges to be mastered and to engage in solution-oriented strategies to learn and develop – rather than to focus on how they will be judged), mastery goals alleviate excessive concerns about image. They focus attention on rectifying a problematic situation or solving a difficult problem, rather than on proving competence (or avoiding judgments of incompetence) and ultimately lead to innovation.How Do Goals On Which We Focus Students’ Attention Impact Classroom Climate?

Particularly in the context of a group, social influences and classroom norms can have significant influence on responses to risk taking or making mistakes in order to learn. When students (or organization members) pursue mastery goals, they are willing to risk displays of incompetence in order to learn and master problems. Mistakes are perceived as a natural part of the learning process- and not as crimes to be punished. In organizations, leaders who set mastery goals often foster team/organizational learning behavior that ultimately leads to innovation. Mastery goals do so by engendering psychological safety in a group that enables members to address differences of opinion openly, challenge assumptions, and admit and discuss mistakes and problems. In the classroom, focusing students’ attention on mastery (learning) goals can create an environment where students feel safe to take interpersonal risks and do not perceive that speaking up or making mistakes will be held against them (all aspects of psychological safety).How Does the Type of Goal We Orient Students Toward Impact Willingness to Take Risks and Learn?

The way instructors “frame” assignments or instructions in class can have a powerful effect on how students orient to learning from mistakes and failure. For instance, in the learning methods section of the syllabus, you might frame the methods in the class with statements like “Use the exercises and problems we work on in class as opportunities to practice new concepts and learn. Think of these as low-risk opportunities where you can make mistakes (the more, the better!) and use the mistakes as helpful information to learn what you can do differently.” You might create “low stakes” assignments outside of class that encourage students to challenge themselves, take risks, and make mistakes – without fear of significant penalties. There are many ways you can frame goals both inside and outside of the classroom to create a culture of “fearless learning,” as described in the video below: “No student should be afraid of learning.” For more information on mindsets, the book “The Science of Lay Theories” is also informative.Videos

Growth Mindset: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It MattersNo Student Should be Afraid of Learning: David Paunesku, TedX Spokane

Websites and Tools

■ The College Transition CollaborativeBooks

■ The Science of Lay Theories: How Beliefs Shape our Cognition, Behavior, and Health (Zedelius, Muller & Schooler, 2017).

- Science of Mindfulness

How and Why Does Mindfulness Impact Learning?

Research has shown that mindfulness practice boosts the brain’s attention networks, and mindfulness is associated with improved sleep, concentration, and decision making. Mindfulness has this impact because it 1) strengthens connections among regions in the brain associated with focusing attention and 2) activates regions associated with awareness in the prefrontal cortex. Cognitive neuroscience researchers have shown the importance of attention and working memory in learning; attention enables students to select relevant information and working memory enables that information to be retained. In the video below, cognitive neuroscientist Amishi Jha describes recent studies on the science of mindfulness and its relationship to attention and learning.Videos

Mindfulness: The Muscle of Attention, Dr. Amishi JhaTraining the Brain to be More Attentive; Cane Talks – Dr. Amishi Jha

- Science of Self-Authorship and Self-Regulation

- Cognitive Influences on Learning

What are Strategies for Optimal Learning?

Have you ever heard this comment from a student who has shown up for office hours? “I don’t understand how I failed the exam. I came to every class. I took notes. I read the book. I highlighted. I studied for the test by reading back over everything. What else could I possibly have done?”In recent years, cognitive scientists have learned a great deal about the basic mechanisms of attention and memory, and the roles they play in student learning. These findings have led to rigorous, evidence-based classroom strategies for enhanced student learning, and techniques students can adopt on their own to prevent illusions of learning like those experienced by the well-intentioned student above. In this section, we discuss strategies and techniques that harness what is known about learning and memory to improve student outcomes.

Example: The Testing Effect

We often think of assignments (especially quizzes and tests) as means of assessment: Did they learn? Did they understand? Can they apply it? One of the most robust findings from the cognitive science of memory is that an encounter with testing materials can be an event of learning no less than a moment of assessment. The reason is that learning begins with the quality of “encoding” — the degree to which a student fully engages their attention with material (in class, in print, online), processing the ideas deeply, thinking about how the material relates to what they already know, previous course concepts, content from other classes, their own life experiences, a movie they watched, a comment from a friend, etc.As such, being familiar with a concept, or even following a concept in class (or as they read), is only a provisional step: it is not the same as learning the concept. For instance, a student may follow along during an interesting class session, but unless they are challenged to think deeply about the material (to encode deeply), they may come away feeling that they know more than they really do. A student may read a textbook paragraph over and over, but if they are distracted, or are only attending to surface details (e.g., bold print), or just skimming to quickly complete an assignment, their encoding will be impoverished, and so will their learning. Such “studying” results in a fragile retention that easily dissolves into a fog of familiarity where the learning lacks depth, specificity, and genuine comprehension. Testing or quizzing—any form of retrieval practice—can help reveal gaps in student understanding, and help orient them toward better learning (the need for more elaborate encoding, and the need to organize and integrate what they are learning).

“The finding that rereading textbooks is often labor in vain ought to send a chill up the spines of educators and learners, because it’s the number one study strategy of most people—including more than 80 percent of college students in some surveys—and is central in what we tell ourselves to do during the hours we dedicate to learning. Rereading has three strikes against it. It is time consuming. It doesn’t result in durable memory. And it often involves a kind of unwitting self-deception, as growing familiarity with the text comes to feel like mastery of the content. The hours immersed in rereading can seem like due diligence, but the amount of study time is no measure of mastery.” (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014, Make it Stick)

To reliably wire a new concept into the circuitry of the brain, the mind needs to work with it, anchor it in the context of existing background knowledge, position it in relation to similar ideas, and form new associations with our experience. Doing this is effortful, of course, but effortful encoding is the most reliable path to stable learning. Hence a mantra that may be familiar to you: The one who does the work does the learning (Doyle, 2008).

Effortful testing can facilitate this. Testing or quizzing—any form of challenging retrieval practice—requires students to grapple with partial/imperfect understanding, to juggle retained fragments and piece them together into something coherent (as best they can), to think about how ideas apply to novel circumstances. This effort to make sense of things is a form of elaborate encoding that helps to form new associations, clarify ideas, confirm and consolidate previously stored memories, and thereby stave off normal forgetting. And if retrieval practice is implemented through low-stakes or no-stakes exercises (e.g., a quiz worth few or no points), it frees students by keeping the focus on learning rather than points.

Effortful testing can facilitate this. Testing or quizzing—any form of challenging retrieval practice—requires students to grapple with partial/imperfect understanding, to juggle retained fragments and piece them together into something coherent (as best they can), to think about how ideas apply to novel circumstances. This effort to make sense of things is a form of elaborate encoding that helps to form new associations, clarify ideas, confirm and consolidate previously stored memories, and thereby stave off normal forgetting. And if retrieval practice is implemented through low-stakes or no-stakes exercises (e.g., a quiz worth few or no points), it frees students by keeping the focus on learning rather than points.“Mastering the lecture or the text is not the same as mastering the ideas behind them. However, repeated reading provides the illusion of mastery of the underlying ideas. Don’t let yourself be fooled. The fact that you can repeat the phrases in a text or your lecture notes is no indication that you understand the significance of the precepts they describe, their application, or how they relate to what you already know about the subject.” (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014, Make it Stick)

How Can We Facilitate Learning via Retrieval Practice?

Course Design ∣ Course Facilitation

Course Design

Some websites with recommendations for course design, implementation guidelines, and links to peer-reviewed literature for further explanation.■ Retrieval Practice

■ Learning Scientists Additional suggestions to keep in mind:

Additional suggestions to keep in mind:

■ Be direct and explicit in your syllabus (and in class) about why you have embedded opportunities for retrieval practice (e.g., practice quizzes) into your course. When students know that these assignments or policies are there for them, as evidence-based mechanisms to aid their learning, and they know why they work, it will bolster student acceptance of the overall plan and sometimes even encourage the use of those strategies outside of class.■ Often, low-stakes retrieval practice works better than no-stakes retrieval practice. While there is nothing wrong with making optional practice tests available, often students lacking extrinsic motivation (e.g., the opportunity to earn points) will not avail themselves of those resources. By requiring students to complete the same materials but for a small number of points, student won’t ignore them (because there are consequences) yet the points are so few that it steers the focus toward learning rather than a preoccupation with points.

■ You may hesitate to include more “testing” given that many students already struggle with test anxiety. The truth is, test anxiety is typically reduced through retrieval practice. Why? Because when students have lots of exposure to retrieval practice before the exam, they learn where the gaps are in their understanding, and can go back and review, ask questions, etc. They walk in on test day with less uncertainty about what will be covered and know before they sit down whether they have a good command of the material.

■ Perhaps most important: retrieval practice can take practically any form. It doesn’t matter—per se—whether retrieval questions are multiple-choice, short answer, or essay; whether they are ask for definitions vs applications; or whether they require responses to a video, news article, or a cartoon. The sky is the limit when it comes to the format. What matters most is that the retrieval practice is effortful. It should aim to meet student learning where it is and gently challenge/stretch their comprehension in new ways.

Course Facilitation

Some websites with recommendations for course facilitation, implementation guidelines, and links to peer-reviewed literature for further explanation.■ Retrieval Practice

■ Learning ScientistsAdditional suggestions for course facilitation:

■ Students should know that there is nothing wrong with re-reading, per se. Going back to “old” material with “new” eyes after a period of time can bring new associations, new insights, new organization to the material: new (more!) learning! But re-reading becomes a needless handicap with diminishing returns when it is repetitious and/or replaces other techniques (retrieval practice) that can better augment the learning already garnered from reading.■ Traditional quizzes are fine as long as the questions seek the level of competence desired (rote knowledge of definitions vs. deeper conceptual knowledge vs questions requiring knowledge transfer/application to a novel domain vs generation questions where students think of examples where ideas could be applied or extended).

■ Quizzing can be used to provide well-timed breaks between lecture or other class activities and can be “gamified” with apps like Socrative or Kahoot!

■ Showing a funny cartoon or a movie clip (etc.) can be a great springboard for engaged reflection, and thus retrieval practice. Make sure all students are required to respond initially (e.g., in writing) even if there is going to be open discussion, because the point is to engage all students in effortful recall: to affirm (consolidate) their understanding of already learned information, to prompt further organization or re-organization of information by forcing students to express ideas intelligibly (in writing or verbally), and foster additional elaborate encoding by challenging students to apply/interpret in the analytic exercise.

Interested in Learning More? Check out these resources.

VideosTesting Effect

Spacing Effect

Stephen Chew Video Series: How to Study

Daniel Willingham Videos: Science & Education:

danielwillingham.com/videos.htmlBooks

Articles

Teaching the Science of Learning (Weinstein, Madan, & Sumeracki, 2018)Optimizing Learning in College: Tips from Cognitive Psychology (Putnam, Sungkhasettee, & Roediger, 2016)

Tools/Guides

Strengthening the Student Toolbox: Study Strategies to Boost Learning (Dunlosky, 2013)The Science of Learning (Deans for Impact, 2015)

Learning Scientists Downloadable Materials

Websites

Retrieval Practice

Learning Scientists

- Biological Influences on Learning

Science of Health & Learning: Sleep, Exercise & Memory

Overview

Sleep plays a critical role in memory, learning, and health – and is a free resource available to all college students (and faculty)! Sleep consolidates memories by reactivating experiences stored in the hippocampus and shifts them for permanent storage in the cortex. Studies have shown that students recall information better after a good night’s sleep than after being awake for several hours. More commonly, college students are often chronically sleep deprived, and studies have found that sleep deprivation leads to difficulty in studying, irritability, and the tendency to make mistakes. Some of the best advice we can give our students is to get around 8 quality hours of sleep a night and to space their retrieval practice over time (rather than staying up late and “cramming” for an exam.) Cardio exercise has also been shown to promote sleep and memory. If you are interested in learning more about the science of sleep and exercise, Walker’s book on sleep and Ratey’s on the science of exercise are informative.Video

Dr. Matt Walker: How lack of sleep affects health and tips for a good night’s restBooks

■ Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster.■ Ratey, J. (2008). Spark: The revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. New York, New York: Little, Brown, & Company.

- Macro Level Influences on Learning: Classroom Climate and Institutional Culture

The Science of Learning: Classroom Climate and Institutional Culture

Given that universities are institutions of higher learning, it is particularly relevant that we model the behaviors necessary to create and sustain an organization that learns. In this section, we provide insights from the science of learning as it applies to individual and collective learning – and the thinking dispositions required to create a learning culture in which the organization learns and adapts to challenges in the environment. We pose questions to consider in creating and designing a learning climate and culture. Critical to these considerations is an understanding of organizations as interrelated systems.Organizations as Interrelated Systems

To facilitate learning in the classroom and throughout the institution, we must first consider that learners are biopsychosocial systems. As noted previously, we don’t learn in a vacuum. At any given moment, our thoughts, actions, and motivations represent the convergence of multiple systems and environmental factors. Each of us is a complex system that is part of a larger social system. Each of us is composed of systems (such as nervous systems and body organs) which are composed of still smaller systems (cells, molecules, atoms). But, we are also influenced by external systems – the classroom climate, institutional culture, and societal influences on higher education such as the political, economic, and global climate and technological innovation. A system approach (asking: how will each change in the system affect other parts of the system?) is critical in creating a sustainable learning culture that can adapt to changing demands and innovate – whether it be in the classroom or the institution overall.In this section, we offer questions (rather than answers) to consider in designing a climate for learning in the classroom as well as in creating an institutional learning culture. But, first, a short survey on your perceptions of learning culture.

Learning Organization Survey

As a starting point, we invite you to take the short learning organization survey below. You can take the survey from your perception of your department or from your perception of the university as a whole. At the end of the survey, you will be provided with your scores for each of the building block categories of a learning organization. For comparison, you can see benchmark scores from other learning organizations.Learning Organization survey with national norms

What are the Building Blocks of a Learning Organization?

The learning organization survey is intended to be a helpful tool to assess the depth of learning in an organization. The goal of the tool is to promote dialogue, not critique. Once you have obtained your scores online, you can identify the quartile in which your scores fall, and identify areas of excellence and opportunities for improvement. You can take the survey to get a quick sense of your work unit or organization. Alternatively, several members of a unit can each complete the survey and average their scores.The learning organization survey is best used not merely as a “report card” but rather as a tool to foster learning. The tool can help you answer two questions:

-

1) To what extent is your unit or organization functioning as a learning organization?

2) What are the relationships among factors that affect learning in your unit or organization?Three broad factors (or building blocks) are essential for organizational learning and adaptability:

1) A supportive learning environment.

-

a. Psychological safety – Do organization members feel comfortable speaking up, presenting a minority viewpoint, sharing a different perspective from that of colleagues or leaders, taking interpersonal risks, and owning up to mistakes without fear?

b. Appreciation of differences – Do organization members recognize the value of opposing ideas and alternative views to spark fresh thinking and innovation?

c. Openness to new ideas – Do members in the organization are encouraged to take risks and explore the untested and unknown?

Time for reflection – Does the learning environment allows time for a pause in the action and thoughtful review of the organization’s or group’s processes?2. Concrete learning processes and practices. Are there processes set up for experimentation, information collection, analysis, professional development, and information transfer/sharing?

3. Leadership that reinforces learning. When leaders actively question and listen to organization members and prompt dialogue and debate, people in the institution feel encouraged to learn. If leaders signal a willingness to entertain alternative points of view, members feel emboldened to offer new and innovative ideas.

How to Build a Classroom Climate for Learning: Questions to Consider

How to Build a Classroom Climate for Learning: Questions to Consider

To build a classroom climate for learning, we must first make explicit what is usually implicit. Take, for example, the implicit belief that “you’re either born with intelligence or not” (a fixed mindset) or the belief that intelligence can be developed by using error as diagnostic information on how to improve and master information (a growth mindset). Ask a student if they believe that intelligence can be developed. The question requires the student to make something explicit that is usually implicit (their beliefs and assumptions about intelligence). Students may often respond, “Well, yes. Of course. That’s what students do in college – develop their intelligence.”But their behavior may suggest otherwise. If they have failed several assignments in a course, they may begin to make attributions, “Well, I’ve never been an ‘English person.’ Some people just aren’t born writers. I didn’t get the writing gene in my family.” Or “I’ve never been a ‘science person.’ I just don’t get anatomy. As soon as this semester is over, I’m changing my major.” The implicit belief that “intelligence or ability is innate; you’re either born with it or you’re not” can have a powerful influence on students’ behaviors in the classroom and the choices they make.

What about us as faculty? How do our beliefs and assumptions influence the classroom learning climate? Ask a faculty if we believe that the learning process is a shared responsibility between students and the instructor. We might answer, “Well, yes. Of course. It’s important for students to become independent thinkers and take responsibility for their learning.” Yet, our behaviors may sometimes indicate otherwise. In an introductory course, for example, we might provide students with a study guide for each exam, rather than teaching students how to create their own study guides to identify the most important concepts or co-creating the study guide together. We may assume that students have not yet developed the capacity to make decisions about what is important, and so, with good intentions, we (as the expert) provide a list of the concepts they must know.

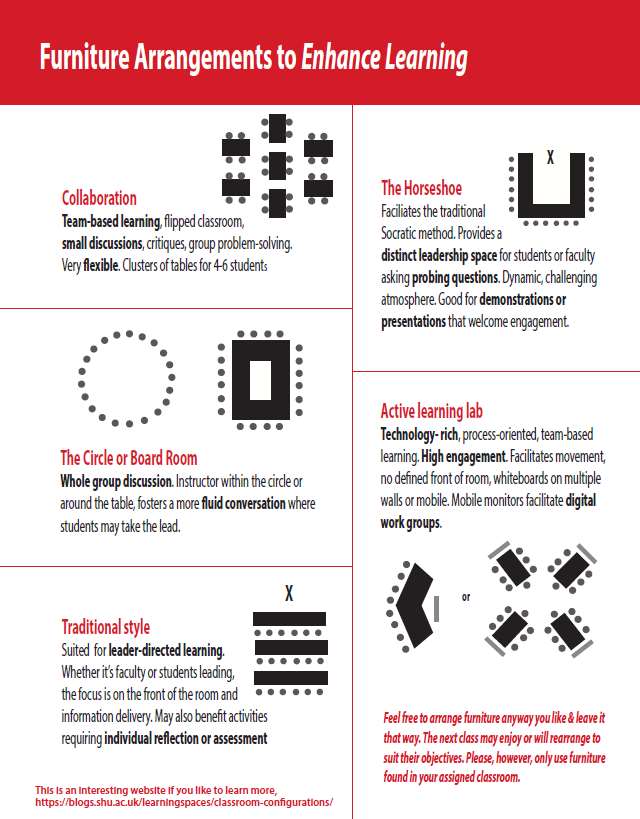

How then can we, as instructors, challenge and reframe our assumptions to engender a climate for learning? The following examples are ways we can use our course syllabi, assignments, assessments, or our physical classroom setup as artifacts on which to reflect to examine our own beliefs and assumptions about the learning process. As you examine these artifacts for your own courses, you can ask yourself questions such as the following:

■ What are the assumptions I must be making for my syllabi, assignments, assessments, and physical space classroom set-up to look as they do?

■ Do the assumptions reflect a mastery (learning) orientation – or a “prove performance” orientation?

■ Am I making an assumption that knowledge is the purview of experts – or that the learning process is a shared responsibility?

■ Am I assuming that it’s my responsibility to provide students with the right answers- or to teach them to ask the right questions and discover the answers?

■ What other assumptions are embedded in my course design?Some examples of artifacts to reflect on . . . . . .

Course Design

Consider the standard syllabus phrase, “Schedule is subject to change at the discretion of the instructor to accommodate instructional and/or student needs.” Notice the assumptions that may be embedded in this phrase – that the instructor is the expert who knows when learning outcomes are not being met and takes sole responsibility in revising the syllabus when needed to accommodate learning needs. A reframe might be something like, “This course schedule may be adapted, as jointly decided, to ensure understanding of course learning outcomes.” Embedded in this phrase is the assumption that decisions about the learning process are a shared responsibility that requires an open conversation between students and the instructor, in which they jointly determine the best way to proceed throughout the course to ensure learning occurs. This alternative phrase may signal to students at the outset that you will be supporting them throughout the course to make a transition from relying on external formulas (from experts) to taking a more co-constructed, self-directed approach to learning. Course Assignment

Course Assignment

Have you set up low stakes, incremental, developmental assignments within the course that allow room for students to take risks, experiment, make mistakes, and learn? Or are there a few assignments that are worth a large percentage of the total grade, where there may be less perceived room (to the student) to experiment, take risks, and potentially fail? Do you provide opportunities for students to revise and resubmit papers in service of mastering knowledge of the topic? Or do students submit the paper once?Do you create authentic learning assignments or projects that have an element of ambiguity – where students must become comfortable with making decisions and thinking critically? Or are the assignments relatively structured, with given parameters that minimize ambiguity? Do you allow students to select topics that they are interested in for projects or papers? All these preferences may indicate your assumptions about autonomous functioning, the types of goals pursued in the classroom, and the learning process itself.

Course Assessments and Feedback

Do you provide honest, challenging feedback on papers or projects – while concomitantly allowing students to revise and resubmit them? Do you provide feedback about the students’ problem solving process (nice work with critically evaluating the evidence) or about their ability (you have such talent for. . . . )? Do you ask students to self-assess their own participation and jointly determine the grade – or do you make the determination and provide feedback on their participation? These are just a few questions to consider as you reflect on the artifacts of course assessments and feedback mechanisms and the assumptions embedded in them.Physical Classroom Space Set-Up (for on-campus courses)

The physical classroom space set-up itself can indicate implicit beliefs that we hold about the learning process. Each set up may be appropriate for specific learning purposes; however, if you notice a reliance on one set-up consistently across courses, it may reflect assumptions that you hold about the process of learning. What set up do you find yourself using most frequently?

Questions to Consider in Creating an Institutional Learning Culture

Just as assumptions in the classroom can affect the climate for learning, the collective beliefs and assumptions of the organization itself can play a significant role in creating an organization learning culture. What are the assumptions of the organization and the organization members? Is it safe to experiment, take risks, and offer differing perspectives to learn, adapt, and innovate? Are organization members concerned with pleasing others – or with speaking candidly with each other, thinking critically together, challenging each other’s assumptions, and creating innovative solutions across boundaries?Psychologist Bob Kegan suggests that “the most forward-looking organizations are those that recognize that a good organization in a certain way needs to be a kind of ‘good school’ – a place for the learning of adults to support their development.” Those organizations ask, “How do I create a culture that will optimally support the ongoing development of all of our people?” (Available from youtube.com/watch?v=6CU2CCdV9sU).

The learning organization survey provides a window into the systems and structures that support an institutional learning culture that can adapt to changing demands and innovate: https://hbs.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_b7rYZGRxuMEyHRz

Learning cultures can be shaped by primary embedding assumptions and secondary reinforcement mechanisms. These can be used as artifacts on which to reflect to examine underlying collective assumptions.

Primary Embedding Assumptions

■ What does the organization pay attention to and measure on a regular basis?

■ How does the organization allocate resources?

■ How does the organization react to critical incidents and crises?

■ What are the processes for deliberate role modeling, teaching, and mentoring?

■ How does the organization allocate rewards?Secondary Reinforcement Mechanisms.

■ What is the organization design and structure?

■ What are the organization systems and procedures?

■ What are the rites and rituals of the organization?

■ What assumptions are embedded in the design of physical space, façade, and buildings?

■ What are the stories about important events and people in the organization’s history?

■ What are the form statements of organization philosophy, creeds, and charters?The STAR model is the framework for features of the organization system that contribute to the organization’s culture and effectiveness. For an organization to be effective, all features (strategy, structure – the location of decision-making power, process – allocation of resources, information flow, management practices and processes, rewards, and people – mindsets and skills of organization members and HR policies of recruitment, selection, promotion, and talent development) must interact harmoniously with each other to communicate a clear, consistent message. All of these design features need to be considered in creating a learning culture in which the organization can effectively adapt, learn, and innovate.

Interested in Learning More? Here are few books, articles, and videos to get started.Videos

Culture of Innovation

Developing a Culture of “Fearless Learning” – Growth Mindset

Developing a Self-Authored Culture

Articles and BooksGarvin, D.A., Edmondson, A.C., & Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning organization? Harvard Business Review, March, 109-116.

Smerek, R.E. (2018). Organizational learning and performance: Science and practice of building a learning culture. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Nisbett, R. E. (2009). Intelligence and how to get it: Why schools and cultures count. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Co, Inc.

Edmondson, A.C. (2019). The fearless learning organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Maryville Suggestions on Applying the Science of Learning

This section will provide ongoing suggestions from Maryville faculty and staff, as they relate to the application of the science of learning at Maryville.